We are back in the mountain terrain. In the last post about it I was pretty confident with my approximation of its 3.5e visual style. However, “Theory and practice sometimes clash. And when that happens, theory loses. Every single time.” (L. Thorvalds, 2009). After trying out my design on more complex mountains, I found that tight turns of the flank geometry were rather common and caused notable fanning and self-intersections within the wide dotted flank lines. Even with significant manual optimization, the results were not really satisfactory. Drawing each flank line as an individual line object allows for more fine-grained control of the line placement at the cost of increasing the data size. Given that single mountains can contain hundreds of flank lines this increase might have some impact on the svg size, but at this point I do not see a way around it.

With that in mind, here are the new problems that need to be solved:

- Given an outline and a ridge, how can we place roughly evenly distributed lines between the two?

- How can we adjust these automatic lines to conform to the features on the drawn map?

- Come up with a way to annotate/generate the required data within an svg drawing software (i.e. Inkscape)

Connecting “Outer” and “Inner”

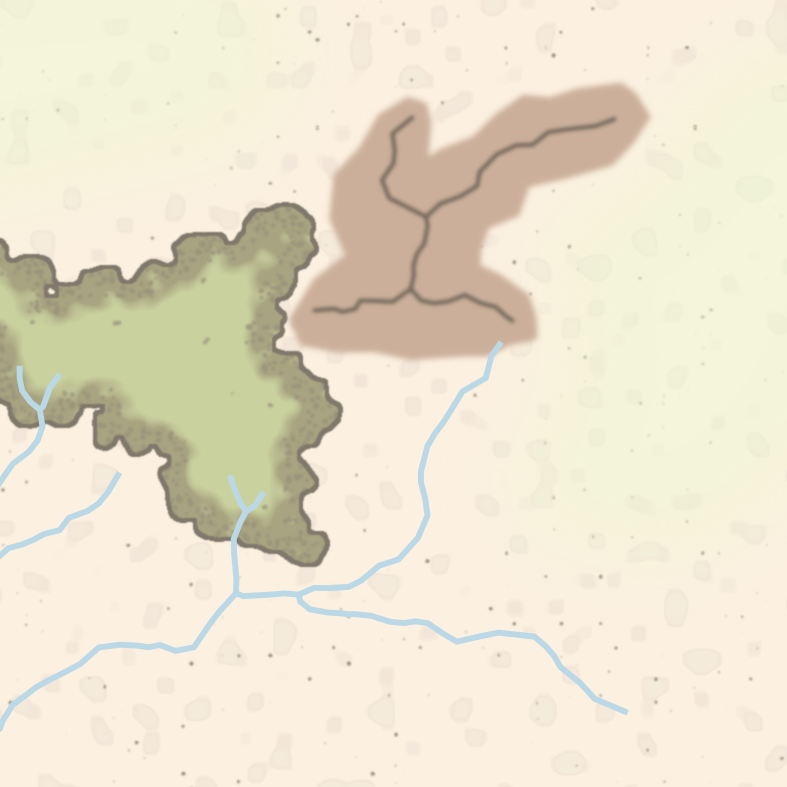

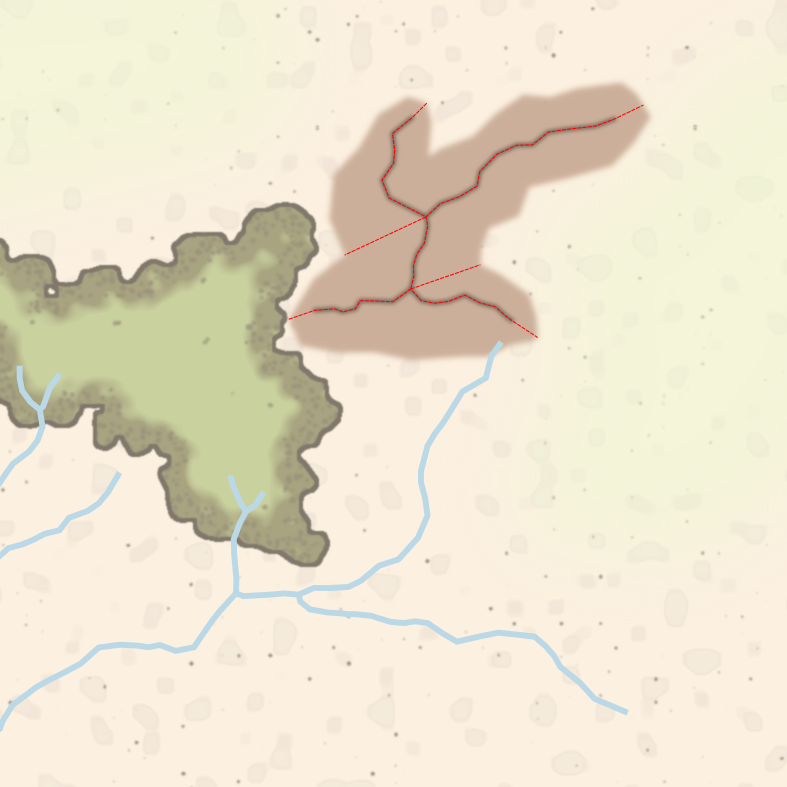

Going back to an uncomplicated example, a basic mountain is defined by an outline polygon and a polyline marking its ridge (We will ignore branching side ridges for now). Flank lines start at the outline, end at the ridge, and are placed roughly equidistant from each other while following the mountain’s shape. Notable exceptions are the ridge endpoints, where several flank lines join at (or at least very close to) the end of the polyline.

One way of simplifying this situation is to treat the ridge line as a polygon with no area. One side of this polygon follows the ridgeline from e.g. the upper endpoint to the lower one, and the other side follows the ridge in reverse, ending at the starting point. Now we have an outer and an inner polygon with the task to draw lines from one to the other. A naive approach would be to define a single flank line as starting point on the inner and outer polygons, then subdivide each polygon into the same number of pieces, and then draw the connections between these subdivisions.

It’s a decent start and, close to the starting flank, things seem to work. However, since the outer polygon does not perfectly follow the shape of the ridge, flank lines get out of sync the farther away they are from the defined starting point.

Oceans

Oceans Plains and Grasslands

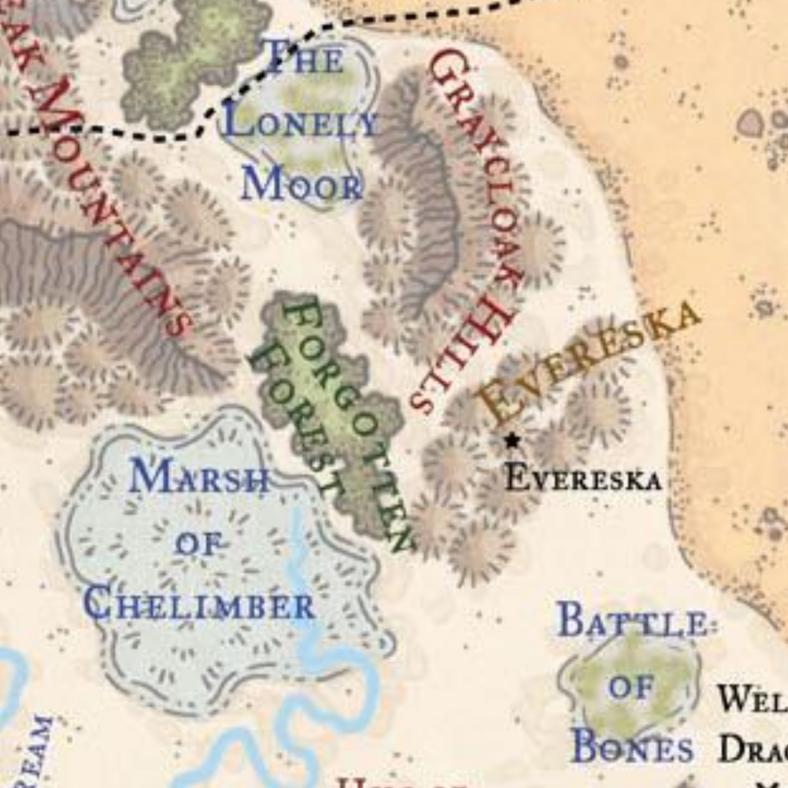

Plains and Grasslands Swamps, Marshes and Moors

Swamps, Marshes and Moors