Mountains Pt. 1 - Reaching the top

It is finally time to tackle the most visually complex terrain type of the 3e map, mountains. The peaks of Faerun are made up of three image components; the outline, which confines the mountains background color, the main ridge line(s), separating illuminated from shadowed sides of a mountain, and the (somewhat) orthogonal flank lines, which connect ridge and outline. It’s the latter that will be the most difficult to approximate, even for simple mountains.

This terrain has a few added twists that make things even harder. A mountain’s background color is influenced by the surrounding terrain, e.g. mountains in forests and jungles might have a greenish tint, while mountains on glaciers sport a white-gray palette. Tall mountains feature white snow areas around their main ridge lines, while volcanoes interrupt the ridge to indicate active craters. Finally, the main ridges may sometimes branch, creating entire side mountains. All of these are special cases that our svg style needs to handle (or at least roughly approximate).

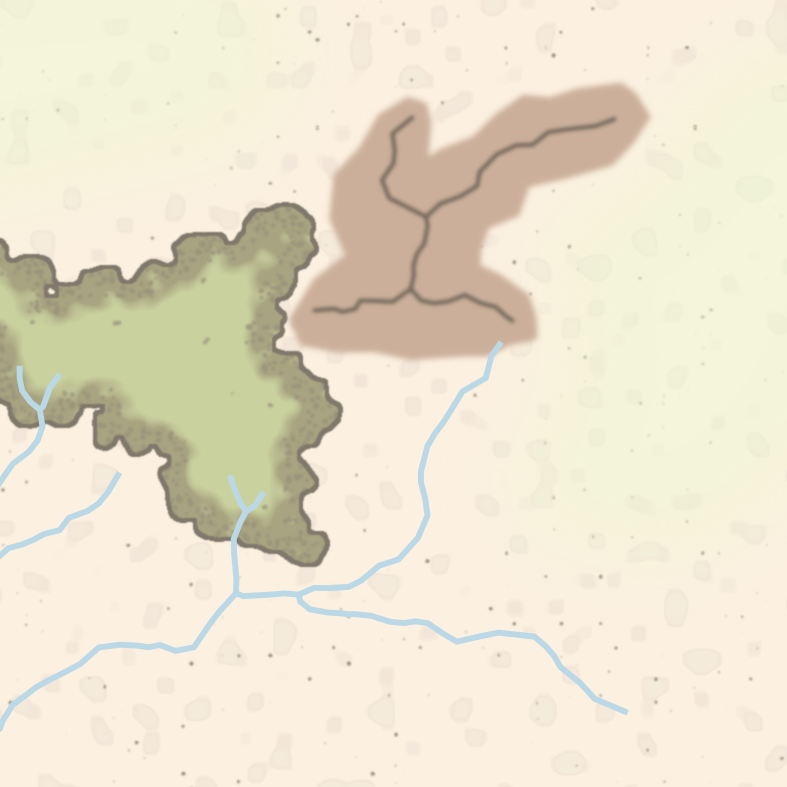

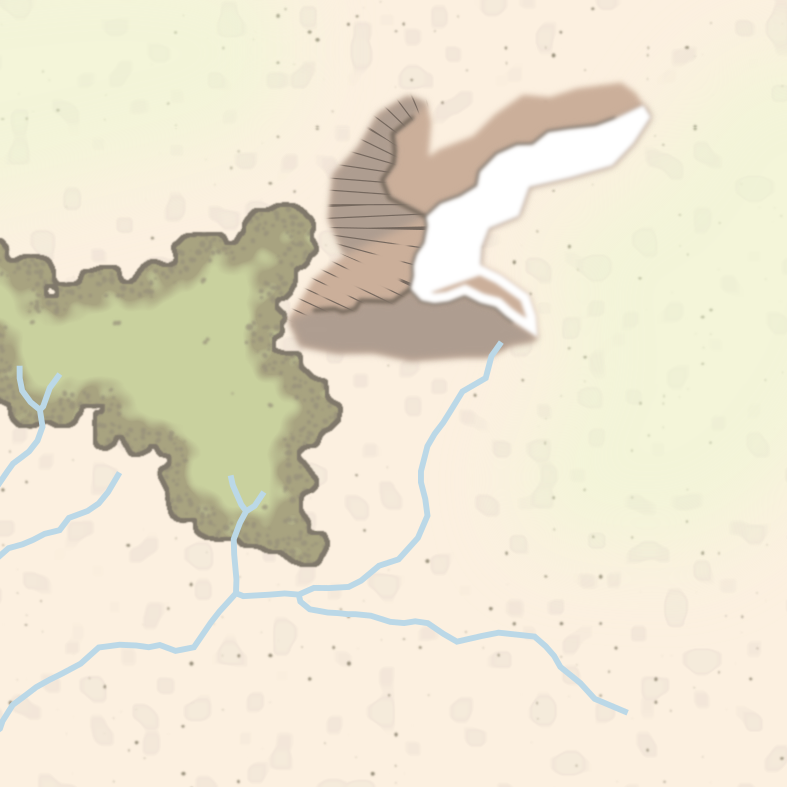

As described in the previous post, we now have access to a programmable svg parser/generator, that we can use to automatically create intermediate features. I will use it to reduce the amount of vector information needed to create visual mountain representations. The idea is to only define outline and ridgeline (with some extra points), and use this data to automatically create all the finer details of the mountain. Before getting to this automatization stage, let’s go over the general concept with a manual example, specifically the Troll Mountains in the east of Amn. We start with the general outline of the mountain area and the branching ridgelines (slightly smooth-filtered to fit with the rest of the map styles):

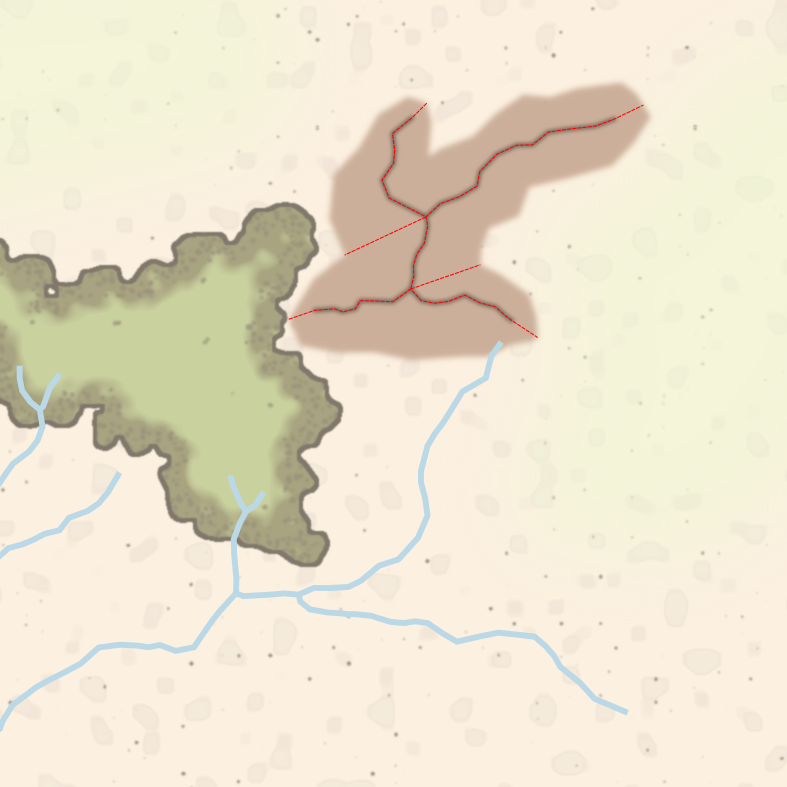

This representation looks obviously completely flat, compared to the original image which uses different color and line features to separate illuminated flanks of the mountain from shadowed ones. The “sun” is located in northeast of the map, so we need to shadow any flanks facing in south and west direction. Branching ridges and steep turns can sometimes introduce a change of lighting within a continuous mountain flank, the Troll Mountains would be split into 6 coloring regions:

If we add some darker shading and blur to the shadowed regions, the visualization gets a lot more “depth”. If we only consider shading changes by branching ridgelines, we can calculate how many separate regions of each color will be present in a single mountain. A simple linear mountain encompasses two flanks, one bright one dark. Every side branch generally creates two more regions of each type. (There are very few cases in which a side branch has the same shadings on both of its sides, e.g. the Snout of Omgar in Samarach, but we will ignore those for now).

Flank lines

With the basic coloring solved we can look at the finer details, i.e. the flank lines. The “brute force” approach to create them would be to draw each individual line as an svg path. This would allow us to recreate the 3e style with very high accuracy, but automatic generation would be difficult and it would massively increase the file size of the map.

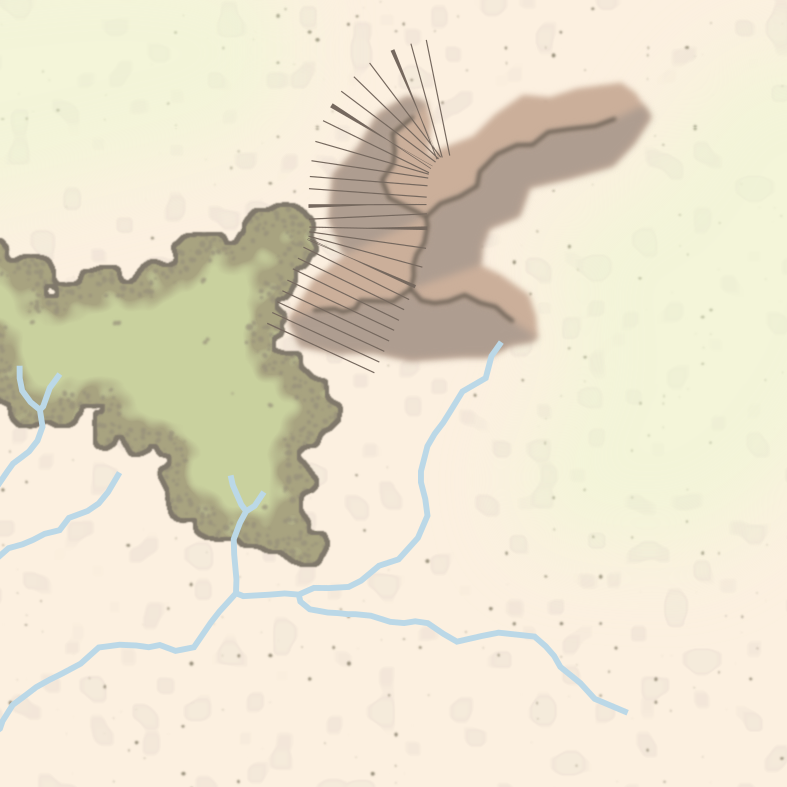

If we give up on some visual fidelity, we can use a few tricks to approximate flank lines with fewer geometric elements. Looking at the lines present on a single flank we observe that they are relatively straight lines (with some jitter), often nearly parallel to each other, and roughly orthogonal to a smoothed-out ridge line. Rather than treating them as individual paths, we can treat the entire set of flank lines as a single wide line with many breaks to form individual straight segments. We can place this stippled spline curve in the middle of flank, so that it covers the entire area while following the shape of the ridge:

This trick has some limitations, the main one being that the stippled sections are not lines with a continuous thickness, but polygons with a different width at each end. If the flank is relatively straight, these width differences are hardly noticeable. At tight curves, however, the sides of stippled sections tend to diverge like a wedge on one side and cross over with each other on the other side. This effectively limits how wide of a line we can use for this and how tight turns can be. It also cannot replicate situations where flank lines are not orthogonal to the ridge for extended lengths.

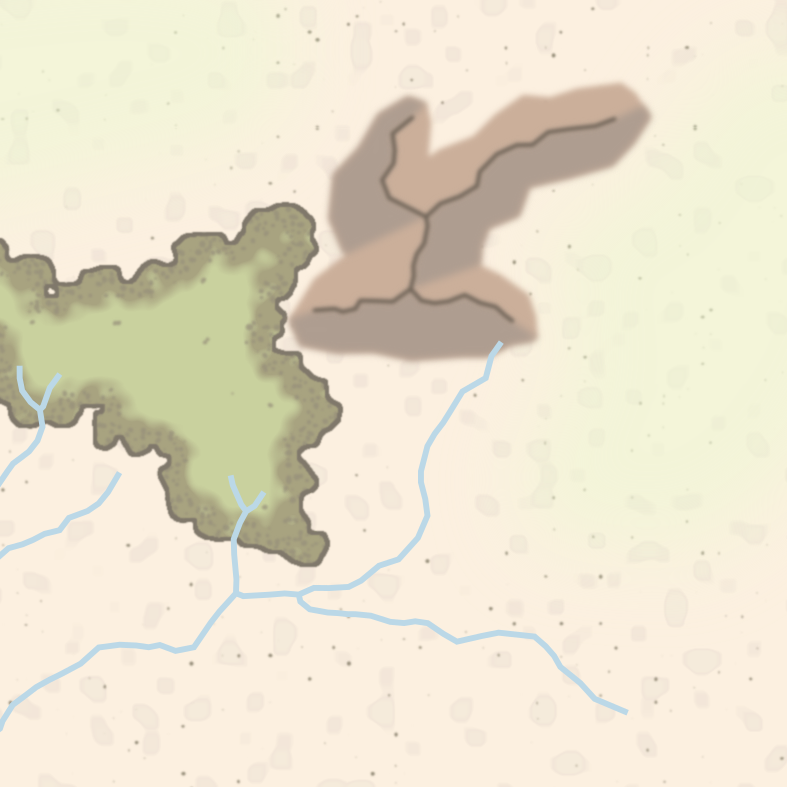

Still, this method is good enough to move forward with it for now. The initial example shows that the stippled line has a fixed width and is wide enough to cover the entire mountain flank. We can use mask shapes based on blurred flank polygons to cut away any overshooting lines. The mask is created from the flank polygon with a shrink version of the bright side polygon used as a hole, to simulate the same effect in the target image (see an example of the mask in white):

The final step is to give the lines a more hand drawn feel, to match the target style, but also to obscure any line width differences. This is done by using applying a displacement filter based on a properly scaled turbulence map. With dilation and blur we have some control over the line thickness, creating the following output style.

Tall mountains

Taller mountains with snow-covered ridges are not difficult to create with this style. We just duplicate the ridge lines, increase its width, change its color to white and apply a generous blur filter. Placed right under the original ridge line, we get a decent approximation of the “tall mountain” style.

We now have a concept on how to draw mountains. However, it is reliant on a lot of geometric objects that have some overlap. Since it would be cumbersome to create all these objects manually, we will have to come up with a way to automate this process. But that is a story for part 2.